Canada’s class struggle

By Baisakhi Roy

New Canadian Media

When 14-year-old, grade 9 student, Hadiya M. — whose name has been changed to protect her privacy — chose to talk about the Quebec mosque attack as part of a social studies presentation, her teacher suggested that she could focus on the more positive aspect of living in Canada.

Hadiya says her teacher “had the audacity” to suggest a story along the lines of a Muslim student who’d immigrated as a refugee from Syria and had therefore mentioned, “what an accepting country Canada is.”

“The teacher was completely oblivious to the fact that the Syrian girl had been constantly ridiculed by some students in our school for being from a ‘war torn’ country and how that entire region was always fighting,'” Hadiya says.

“I was confused when she said that I should ‘tone down’ my presentation. Anyway, I did not want all that attention, so I just skipped the Quebec part and spoke about other topics like the different festivals that are celebrated in Canada.”

Hadiya, who identifies as both Black and Muslim, says she’s faced questions about her faith that seem innocent on the surface but are clearly racist to her.

“I mean, how hard is it to Google that the Muslim place of worship is called a mosque and is different from the gurudwara, for example, which is where people of the Sikh faith pray?” she says. “Some people are just racist at their core and they will never change.”

Hadiya is one of many racialized Canadian school children who report witnessing or experiencing racism at their schools.

A recent study conducted by the non-profit Angus Reid Institute in partnership with the University of British Columbia revealed that some children, particularly “those who identify as a visible minority (are) struggling to fit in” with their peers. They are three times as likely as white children to say that they have faced personal abuse. Indigenous children are twice as likely to say this.

According to the study, a majority of children — 58 percent — say they’ve seen kids insulted, bullied or excluded based on their race or ethnicity, and another 14 percent say they’ve experienced it themselves.

Notably, discussions with 12- to 17-year-olds about their experiences with diversity and racism at their school, found that ethnically diverse areas of the country had more incidents of racially motivated bullying and slights.

But the study also mentions that children in more diverse schools are significantly more likely to say they have learned about racism in Canada’s history, Indigenous treaties, residential schools, and multiculturalism, than those who say their student body is made up of kids from mostly the same background.

To Dr. Henry Yu, a history associate professor at UBC and a member of the National Forum on Anti-Asian Racism in Canada, this doesn’t surprise him “at all.”

He says while more diversity would presumably invite fewer incidents of racism, it’s important to look at how the history of multiculturalism and thus of racism in this country is being taught.

Without honestly discussing the “long history of racism, of white supremacy,” students only get a whitewashed version of multiculturalism in which “we all get along,” says Yu, “which can actually serve to suppress an awareness of racism. It’s almost like a cover story for who we actually are.”

Yu says there might be an undercount in the study, particularly in a place like Saskatoon, “which is relatively less diverse than other parts of the country, but still, it’s still a fairly solid assessment” given the kind of data it has recorded.

In Canada, diversity varies significantly by province. While Atlantic Canada has a much lower visible minority population, Ontario and B.C. are the most racially diverse provinces. Quebec is the least racially diverse of the most populous provinces in the country.

The poll comes in the wake of the recent Multiculturalism@50: Diversity, Inclusion and Eliminating Racism conference where participants unequivocally acknowledged that hate crimes in Canada were a direct threat to the ideals of multiculturalism.

“Now, in Canada, more Muslims have been killed in targeted hate attacks…than any other G7 country in the past five years because of Islamophobia, so this is having real impacts,” said Amira Elghawaby, director of programs and outreach at the Canadian Race Relations Foundation (CRRF), during the conference.

While some of the findings in the Angus Reid study are encouraging — nine in 10 youth responders say they talk to parents and family about racism — some others are more concerning.

Among the most concerning are 44 percent saying other kids don’t care or pretend racist behaviour is not happening, and a small number (7 percent) say other kids actively encourage these behaviours. One-quarter of kids say teachers ignore racist behaviour or are not aware of it. A majority of children report witnessing or experiencing racism at their schools. And 58 percent say they’ve seen kids insulted, bullied, or excluded based on their race or ethnicity, while another 14 percent say they’ve experienced it themselves.

“Kids are bullied routinely, even on Pink Shirt Day, which is Anti-Bullying Day. It’s all okay to celebrate Multiculturalism Day at school, but not everybody knows what it really means,” says Hadiya. “And, honestly, some don’t even care to find out.”

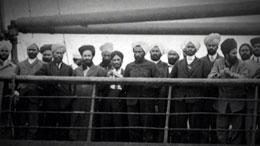

According to the study, one-third of the students say they’ve never learned anything about slavery in Canada, half say they didn’t learn of the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War, three-in-five say schools didn’t teach them about the head tax on Chinese immigrants, and four-in-five say the Komagata Maru incident never came up in their classrooms.

Yu stresses that the way forward is to ensure the education system acknowledges the history and role of racism in Canada. Without it, it’s hard to “deal with these legacies effectively.”

Yu says it’s up to teachers to help students learn about racism. If students fail to “grapple with these issues,” it’s a reflection of a system that’s failing to equip “our teachers with the necessary tools.”

“What we are not learning in high school is the thing that actually disturbs me,” he says. “It’s an issue that needs immediate attention.”

The Angus Reid study is based on an online survey conducted in August of this year among a representative randomized sample of 872 Canadians aged 12 to 17, whose parents are members of Angus Reid Forum.