Canada wades in on South China Sea dispute

Canada’s condemnation of China’s military actions in the disputed South China Sea is likely to complicate warming relations between Manila and Beijing, political analysts said.

The Philippines is a major claimant in the disputed area, saying it has geographical proximity to the Spratly Islands.

China claims 90 percent of the potentially energy-rich maritime territory and has been building on and militarizing rocky outcrops and reefs in its waters.

Both Philippines and China also lay specific claim to the Scarborough Shoal (known as Huangyan Island in China) - a little more than 100 miles (160km) from the Philippines and 500 miles from China.

Brunei, Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam also lay claim to parts of it, through which about $5 trillion of trade passes each year.

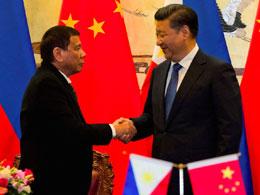

China and the Philippines are now considering a series of resource-sharing agreements in the South China Sea, the latest development in a diplomatic warming trend.

The new China-Philippines proposal is expected to face fierce resistance in Manila, where prominent military, political and nationalistic civil society figures remain skeptical of China’s broad intentions in Philippine-claimed waters.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte last week offered a sharing deal with China on joint exploration in the South China Sea.

In a speech in Davao City, Duterte said he suggested the deal instead of going to war with the Eastern giant.

Amidst this backdrop, the Senate of Canada last week approved a motion which condemns China for its “aggressive and expansive behavior” in the South China Sea.

“By passing this motion, the Senate is stating its concern on China’s escalating and hostile behavior in the South China Sea, and urging the government of Canada to take a principled position on one of the biggest geopolitical conflicts of our time,” The Globe and Mail quoted conservative senator Thanh Hai Ngo, who sponsored the motion, as saying.

“The Asia-Pacific region has recently seen escalating territorial disputes between China and other nations, including Vietnam and the Philippines. In my view, Chinese adventurism and predatory action has been the main threat to the region’s fragile peaceful equilibrium,” said Senator Ngo.

The motion passed Canada’s upper house of parliament 43-28, with six abstentions

The Chinese embassy in Ottawa said in a statement that Ngo was trying to “stir up troubles” in a situation that has been calm.

“This is irresponsible. His purpose is nothing but casting shadows over the China-Canada relations which develop smoothly currently,” the embassy said.

China has repeatedly defended the work, saying it has every right to build on what it considers inherent Chinese territory and that it is building public facilities, like weather stations and typhoon harbors.

In 2016, the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration stated that China has no legal basis to claim sovereignty over territory based on a vaguely defined “nine-dash-line” in the waters and the Canadian government supported the court’s decision.

The Philippines no longer bothers with the decision of The Hague as it seeks closer ties with China, wote Alex Lo, a commentator with the South China Morning Post.

“The South China Sea is calmer today than it was two years ago. The Trudeau government under the Liberal Party is ignoring the motion. Korea is getting all the attention,” he stated.

This is not the first time that Canada has voiced its opinion on the South China Sea issue, said Liu Dan, a research fellow with the Center for Canadian Studies, Guangdong University

“If Canada continues its double standard on international issues and rules and doesn't make a holistic and stable policy on China, this will not only hinder the smooth development of Sino-Canadian relations as well as important issues like free trade negotiations, but prevent Canada from becoming a true leader in the international community,” he wrote in an opinion piece.

Since Senate motions are non-binding, it remains unclear whether the South China Sea motion will have any influence on the policy of the Canadian government, stated Liu Dan.

A look at how the dispute has unfolded:

1947: China demarcates its South China Sea territorial claims with a U-shaped line made up of eleven dashes on a map, covering most of the area. The Communist Party, which took over in 1949, removed the Gulf of Tonkin portion in 1953, erasing two of the dashes to make it a nine-dash line.

1994: The 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, under which the Philippines has taken China to arbitration, goes into effect after 60 countries ratify it. The agreement defines territorial waters, continental shelves and exclusive economic zones. The Philippines joined the convention in 1984, and China in 1996. The U.S. has never ratified it.

1995: China takes control of disputed Mischief Reef, constructing octagonal huts on stilts that Chinese officials say will serve as shelters for fishermen. The Philippines lodges a protest through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

1997: Philippine naval ships prevent Chinese boats from approaching Scarborough Shoal, eliciting a protest from China. The uninhabited reef, known as Huangyan Island in China, is 230 kilometers (145 miles) off the Philippines and about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) from China. In ensuing years, the Philippines detains Chinese fishermen numerous times for alleged illegal fishing in the area.

2009: China submits its nine-dash line map to the United Nations, stating it “has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters.” The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia protest the Chinese claim.

2013: The Philippines brings its dispute with China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, angering Beijing. A five-member panel of international legal experts is appointed in June to hear the case.

2015: The arbitration panel in The Hague rules in October that it has jurisdiction over at least seven of the 15 claims raised by the Philippines. A hearing on the merits of the claims is held in November. China does not participate.

July 12, 2016: The Permanent Court of Arbitration rules that China has no legal basis for claiming much of the South China Sea and had aggravated the regional dispute with its land reclamation and construction of artificial islands that destroyed coral reefs and the natural condition of the disputed areas. The Philippines, which sought the arbitration ruling, welcomed the decision, and China rejected it outright.